Trump et Poutine vont se voir à Budapest

Donald Trump a annoncé jeudi qu’il rencontrerait Vladimir Poutine à Budapest, capitale de la Hongrie, sans donner de date précise, après un échange téléphonique avec son homologue russe au cours duquel “de grands progrès ont été faits” selon lui.Il a fait cette annonce inattendue à la veille d’une entrevue à la Maison Blanche avec son homologue ukrainien Volodymyr Zelensky, lequel espère que Washington lui fournira des missiles Tomahawk malgré les protestations de Moscou.”Il est convenu que les représentants des deux pays s’occuperont sans tarder de la préparation d’un sommet, qui pourrait être organisé, par exemple, à Budapest”, a pour sa part a déclaré le conseiller diplomatique de Vladimir Poutine, Iouri Ouchakov, devant la presse après cette conversation au téléphone.”Nous sommes prêts!” a commenté sur X le Premier ministre hongrois Viktor Orban, allié du chef d’Etat américain.Donald Trump a jugé que son échange jeudi avec Vladimir Poutine avait été “très productif”, le Kremlin parlant pour sa part d’un entretien “extrêmement franc et empreint de confiance”.- Alaska -Ces commentaires signalent un réchauffement entre les deux dirigeants, dont la relation s’était rafraîchie depuis un sommet le 15 août en Alaska, annoncé avec fracas mais conclu sans avancées concrètes sur la guerre en Ukraine.”Nous avons décidé qu’une réunion de nos conseillers de haut niveau aurait lieu la semaine prochaine. Les premières réunions seront dirigées par le secrétaire d’Etat Mario Rubio pour les Etats-Unis” dans un lieu encore à définir, a écrit Donald Trump sur Truth Social.”Puis le président Poutine et moi-même nous réunirons dans un endroit déjà convenu, Budapest, en Hongrie, pour voir si nous pouvons mettre fin à cette guerre +sans gloire+ entre la Russie et l’Ukraine”, a ajouté le président américain.Vladimir Poutine est sous le coup d’un mandat d’arrêt de la Cour pénale internationale, dont la Hongrie a décidé de se retirer mais dont elle reste membre jusqu’à ce que ce retrait soit effectif, le 2 juin 2026. Viktor Orban avait déjà reçu en avril le Premier ministre israélien Benjamin Netanyahu, lui aussi visé par un mandat d’arrêt de l’institution basée à La Haye (Pays-Bas).- Tomahawk -Les missiles américains Tomahawk permettraient à l’Ukraine de frapper loin à l’intérieur du territoire russe, et Moscou a averti qu’une livraison de ces armements à Kiev constituerait une “escalade” à ses yeux.Au moment où la Russie multiplie les frappes contre les infrastructures énergétiques en Ukraine, provoquant des coupures d’électricité, le Tomahawk sera le “sujet principal” de la rencontre avec Donald Trump vendredi, a dit jeudi à l’AFP un haut responsable ukrainien.L’ambassadrice d’Ukraine à Washington Olga Stefanishyna a jugé que les frappes russes dévoilaient le vrai visage de Moscou, accusé de rejeter de facto les efforts de paix en semant la “terreur”. Dans la nuit de mercredi à jeudi, la Russie a tiré une série de 320 drones et 37 missiles, selon l’armée de l’air ukrainienne, qui a souligné que 283 drones et cinq missiles avaient été abattus.Le président américain a laissé planer le doute sur ses intentions.Dimanche, il a estimé que l’utilisation de Tomahawk par l’armée ukrainienne serait “une nouvelle étape agressive.”-Très déçu -Dès son retour au pouvoir, Donald Trump a rompu l’isolement dans lequel les puissances occidentales maintenaient Vladimir Poutine depuis le début de la guerre en Ukraine.Il a de la même façon remis en cause l’aide militaire accordée à l’Ukraine par Washington pendant la présidence de son prédécesseur démocrate Joe Biden.Le président américain, qui s’est toujours vanté d’avoir une relation privilégiée avec son homologue russe, avait d’abord assuré qu’il pouvait mettre fin au conflit très rapidement, avant de concéder que l’entreprise était plus complexe que prévu.Il a récemment estimé, à la surprise générale, que l’Ukraine pouvait remporter la guerre. Il s’est aussi dit à plusieurs reprises “très déçu” par Vladimir Poutine.Le président américain n’a toutefois pas exercé de pression significative sur la Russie pour qu’elle dépose les armes.

Le réseau social Pinterest permet à ses utilisateurs de filtrer des contenus IA

Le réseau social américain Pinterest permet aux utilisateurs depuis jeudi de filtrer une partie des contenus générés par intelligence artificielle (IA) et postés sur la plateforme, alors que beaucoup s’inquiètent d’une déferlante d’images IA standardisées ou médiocres.Le groupe californien dit prendre ainsi en compte les retours de ses usagers, qui “veulent la créativité et l’inspiration qu’ils apprécient, avec le bon équilibre entre les contenus générés par des humains et par de l’IA”, selon un communiqué.Il est désormais possible de régler ses préférences pour voir, dans une catégorie donnée comme la décoration ou la mode, “moins de contenu généré par IA” parmi les photos postées sur le site. C’est le premier réseau social d’importance a offrir la possibilité pour les usagers d’écarter une partie de ces contenus.Sollicités par l’AFP quant à une possible initiative similaire, Instagram, TikTok et YouTube n’ont pas donné suite dans l’immédiat.Depuis le lancement de ChatGPT, en novembre 2022, les outils de création d’images IA se sont généralisés et leur précision s’est sensiblement améliorée.Les contenus IA publiés sur les réseaux sociaux ont augmenté de manière exponentielle, une vague que certains ont qualifié de “bouillie AI” (AI slop), en référence à une production jugée sans imagination, sans créativité et assez standard.En avril, Pinterest avait déjà systématiquement assigné un label “modifié par l’IA” à toute image retouchée par intelligence artificielle.

Le réseau social Pinterest permet à ses utilisateurs de filtrer des contenus IA

Le réseau social américain Pinterest permet aux utilisateurs depuis jeudi de filtrer une partie des contenus générés par intelligence artificielle (IA) et postés sur la plateforme, alors que beaucoup s’inquiètent d’une déferlante d’images IA standardisées ou médiocres.Le groupe californien dit prendre ainsi en compte les retours de ses usagers, qui “veulent la créativité et l’inspiration qu’ils apprécient, avec le bon équilibre entre les contenus générés par des humains et par de l’IA”, selon un communiqué.Il est désormais possible de régler ses préférences pour voir, dans une catégorie donnée comme la décoration ou la mode, “moins de contenu généré par IA” parmi les photos postées sur le site. C’est le premier réseau social d’importance a offrir la possibilité pour les usagers d’écarter une partie de ces contenus.Sollicités par l’AFP quant à une possible initiative similaire, Instagram, TikTok et YouTube n’ont pas donné suite dans l’immédiat.Depuis le lancement de ChatGPT, en novembre 2022, les outils de création d’images IA se sont généralisés et leur précision s’est sensiblement améliorée.Les contenus IA publiés sur les réseaux sociaux ont augmenté de manière exponentielle, une vague que certains ont qualifié de “bouillie AI” (AI slop), en référence à une production jugée sans imagination, sans créativité et assez standard.En avril, Pinterest avait déjà systématiquement assigné un label “modifié par l’IA” à toute image retouchée par intelligence artificielle.

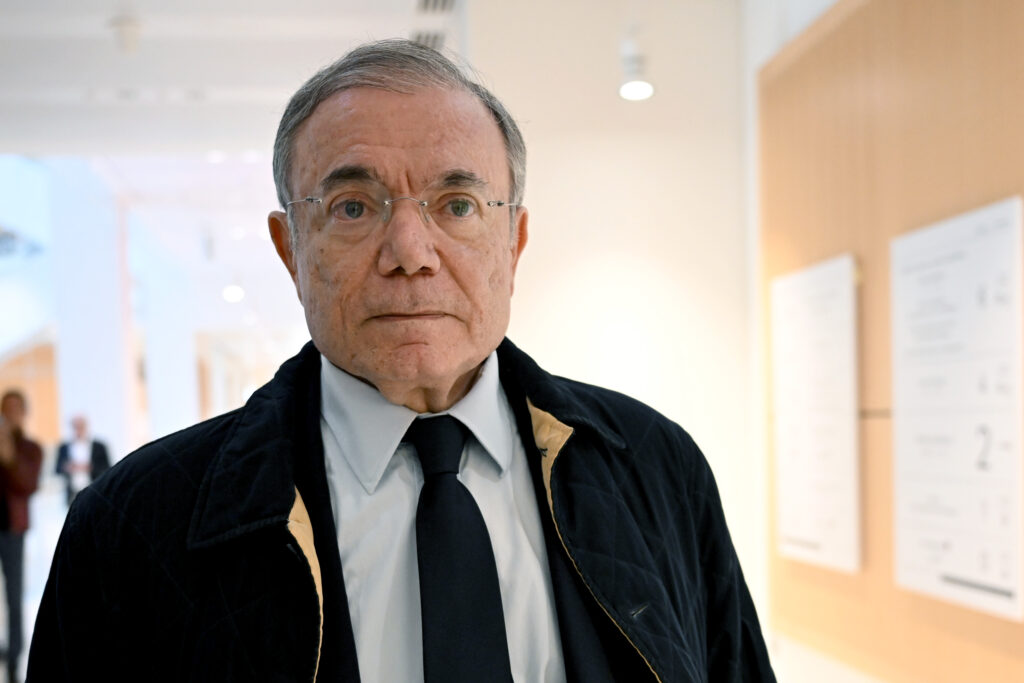

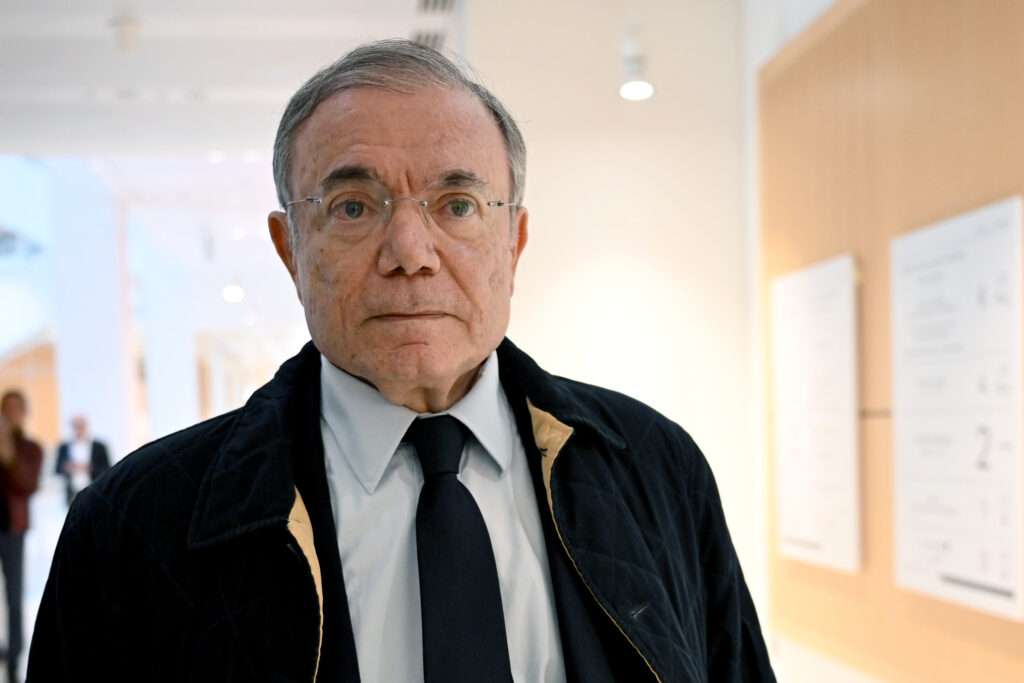

Procès Naouri/Casino: le parquet réclame une condamnation générale

Le parquet a réclamé jeudi la condamnation de l’ex-PDG du groupe Casino, Jean-Charles Naouri, pour manipulation de cours et corruption, soupçonné d’avoir manœuvré pour maintenir artificiellement le prix de l’action de son entreprise en 2018 et 2019.Les peines requises par le parquet national financier (PNF) sont attendues dans la soirée.Les procureurs ont également réclamé la condamnation pour les mêmes infractions du patron de presse Nicolas Miguet, qui avait défendu sans relâche l’action Casino dans ses diverses publications, parfois au mépris de la réalité du marché.Ce dernier, qui s’est forgé une réputation sulfureuse dans les milieux du boursicotage – il a déjà été condamné à plusieurs reprises pour des faits comparables -, avait conclu une “convention” supposément de “conseils” avec le groupe de grande distribution: 823.000 euros de rémunération en neuf mois.Or, “la convention de conseil est à la délinquance en col blanc ce que la valise de billets est au blanchiment de trafic de stupéfiants”, ont ironisé les deux représentants du parquet, qui ont prévu cinq heures de réquisitions pour détailler leurs charges, après huit journées de débat.Jean-Charles Naouri avait accepté de rencontrer Nicolas Miguet en septembre 2018, au moment même où l’action Casino décrochait en Bourse. Vingt-quatre heures plus tard, le contrat était signé.Presque une coïncidence, avaient assuré les deux prévenus à la barre, se bornant à résumer les “conseils” par la création d’un club d’actionnaires – jamais réalisé – ou dynamiser les assemblées générales – sans résultat probant.L’objet de la rencontre et de l’accord, pour l’accusation, est tout autre: “Il y a un stress maximum à la tête de Casino, presque de désespoir: Jean-Charles Naouri sait que son image, sa fortune, sont susceptibles de s’écrouler”, le magnat des supermarchés étant convaincu de faire l’objet d’une attaque imminente et hostile du groupe Carrefour. “Ce qui n’est pas l’objet de ce procès”, a pris soin de balayer le ministère public.”L’intérêt pour Jean-Charles Naouri, c’est de défendre le cours de Casino. Celui de Nicolas Miguet, c’est d’augmenter son chiffre d’affaires: il a gagné à cette période 10.000 abonnés”, rappellent les procureurs.Car M. Miguet dispose de diverses lettres boursières et d’un service Audiotel, dans lesquels il prodigue des conseils boursiers. En l’espèce, durant la période: “acheter, racheter, conserver les actions Casino”.”Ils ont fait des petits porteurs de la simple chair à canon”, ont tonné les deux procureurs, alors que, quelques heures plus tôt, l’avocat d’un agriculteur du Nord rappelait que son client avait “acheté 44.000 actions Casino d’une quarantaine d’euros chacun; cinq ans plus tard, elles valent 0,46 euro”.- “Du grand art!” -Et si “Jean-Claude Naouri avait décidé de tendre un piège à Carrefour”, tous les mis en cause “ont un objectif commun: sauver coûte que coûte le cours de Casino, y compris par des moyens illégaux”, répètent encore les deux représentants du PNF.A propos du chef de manipulation de cours par diffusion de fausses informations – selon les procureurs “créées sur mesure pour les besoins de Casino” -, il a notamment été rappelé le “conseil” de M. Miguet de “feuilletonner” le récit de la contre-offensive de Casino et de la supposée remontée de son cours. Réaction par SMS d’un bras droit de Jean-Charles Naouri: “Du grand art!””Dans ce dossier, la manipulation affleure à tous les étages”, tempêtent encore les deux procureurs, en relevant que Nicolas Miguet avait en outre “un intérêt personnel” à soutenir le groupe en difficulté pour détenir 125.000 actions pendant la période de la convention, soit 3 millions d’euros de valeur: “Il s’est donc condamné lui-même à dire du bien de l’action Casino”.Tombée 2024 dans l’escarcelle du milliardaire tchèque Daniel Kretinsky au terme d’une restructuration spectaculaire de sa dette devenue insoutenable, l’entreprise Casino est également poursuivie en tant que personne morale, ainsi que trois anciens hauts cadres.La défense doit plaider à partir de lundi.pab/cal/dch

Battlefield 6, meilleur démarrage de la franchise, se félicite Electronic Arts

Le jeu de tir à la première personne Battlefield 6 s’est vendu à 7 millions de copies en trois jours, s’est félicité jeudi son éditeur Electronic Arts (EA), qui compte sur lui pour rattraper son retard sur Call of Duty, dont le prochain épisode sort en fin d’année.”Battlefield 6 a atteint des sommets historiques pour les ventes de la franchise pendant les trois premiers jours du lancement, avec 7 millions de copies vendues, et le décompte continue”, a annoncé le studio américain, une semaine après la sortie de son blockbuster, l’un des plus attendus de l’année.Cette performance reste en deçà de records tels que les plus de 11 millions de copies vendues en 24h pour GTA V en 2013 ou le démarrage historique de “Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 3” en 2011 (6,5 millions de ventes le premier jour aux Etats-Unis et au Royaume-Uni, selon son éditeur).Mais c’est une bonne nouvelle pour EA après le lancement jugé décevant de l’opus précédent Battlefield 2042, pour lequel le studio n’avait pas communiqué de chiffres sur le démarrage.Le jeu, disponible sur PC, Xbox et Playstation 5, va touefois affronter dans quelques semaines la comparaison avec “Call of Duty: Black Ops 7”, la franchise concurrente d’Activision Blizzard (Microsoft) qui maintient un rythme de sortie annuel.Battlefield, simulation de combats en vue subjective qui revendique plus de 100 millions de joueurs depuis ses débuts, s’est fait distancer au fil des années par son petit frère Call of Duty, d’un an son cadet.Battlefield 6 situe son action fictive au milieu d’un conflit moderne en 2027 où les Etats-Unis et leurs alliés entrent en guerre avec une milice privée surarmée, Pax Armata, soutenue par des pays européens ayant quitté l’OTAN.

Battlefield 6, meilleur démarrage de la franchise, se félicite Electronic Arts

Le jeu de tir à la première personne Battlefield 6 s’est vendu à 7 millions de copies en trois jours, s’est félicité jeudi son éditeur Electronic Arts (EA), qui compte sur lui pour rattraper son retard sur Call of Duty, dont le prochain épisode sort en fin d’année.”Battlefield 6 a atteint des sommets historiques pour les ventes de la franchise pendant les trois premiers jours du lancement, avec 7 millions de copies vendues, et le décompte continue”, a annoncé le studio américain, une semaine après la sortie de son blockbuster, l’un des plus attendus de l’année.Cette performance reste en deçà de records tels que les plus de 11 millions de copies vendues en 24h pour GTA V en 2013 ou le démarrage historique de “Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 3” en 2011 (6,5 millions de ventes le premier jour aux Etats-Unis et au Royaume-Uni, selon son éditeur).Mais c’est une bonne nouvelle pour EA après le lancement jugé décevant de l’opus précédent Battlefield 2042, pour lequel le studio n’avait pas communiqué de chiffres sur le démarrage.Le jeu, disponible sur PC, Xbox et Playstation 5, va touefois affronter dans quelques semaines la comparaison avec “Call of Duty: Black Ops 7”, la franchise concurrente d’Activision Blizzard (Microsoft) qui maintient un rythme de sortie annuel.Battlefield, simulation de combats en vue subjective qui revendique plus de 100 millions de joueurs depuis ses débuts, s’est fait distancer au fil des années par son petit frère Call of Duty, d’un an son cadet.Battlefield 6 situe son action fictive au milieu d’un conflit moderne en 2027 où les Etats-Unis et leurs alliés entrent en guerre avec une milice privée surarmée, Pax Armata, soutenue par des pays européens ayant quitté l’OTAN.

‘Wonder weapon’? Five things about US Tomahawks coveted by Ukraine

The Tomahawk cruise missile, set to be at the centre of talks between Donald Trump and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, has been a mainstay of the US armed forces for over four decades and repeatedly used with success in the theatre of war.Ukraine is eager to obtain the American missiles which would allow Kyiv to strike deep into Russian territory and give its armed forces a significant boost three-and-a-half years into the conflict sparked by the February 2022 full-scale invasion.Some analysts and observers question if for all the avowed prowess of the Tomahawk it would in any way tip the balance in the war. But their delivery would be a symbol of American support for Kyiv in the wake of the disastrous Oval Office meeting between Zelensky and Trump in February and a strong signal to Russian President Vladimir Putin that Trump is losing patience with Moscow. Trump announced Thursday one day ahead of the talks with Zelensky that, following a call with Putin, he would meet the Russian leader at an unspecified date in Budapest.Here are five things to know about the Tomahawk:- Mainstay of US armed forces – The Tomahawk is a cruise missile that has been in service for 42 years and since then used in almost all US military interventions.Fired from submarines or surface ships, the BGM-109 Tomahawk flies up to 1,600 kilometers (1,000 miles) in range, at 880 km/h (550 mph) and a few dozen meters above the ground.According to US Navy budget documents 8,959 missiles have been produced since the programme began and more than 2,350 have been fired.A version of the Tomahawk carrying a nuclear warhead was retired from service in 2013.- Repeatedly used in conflict – The Tomahawks were first fired in a conflict during the US-led Operation Desert Storm against Saddam Hussein’s Iraq in 1991 and repeatedly in US military interventions since then.Most recently, some 80 missiles were still fired in January 2024 against the Tehran-backed Huthi rebels in Yemen, and another 30 against the Isfahan nuclear site in Iran in June when the US joined Israel’s war against the Islamic republic.The Tomahawk is also in service with the British Navy. Japan decided last year to acquire 400, and Australia and the Netherlands are also considering acquiring them.- Wanted by Ukraine – With its 450-kilogramme explosive charge, the Tomahawk can be used against air defense sites, command centers, airfields, or any heavily defended target.Ukraine could with a Tomahawk target at least 1,655 targets of interest, including 67 air bases in Russia, well beyond Moscow, according to the US-based Institute for the Study of War (ISW).Stacie Pettyjohn, a researcher at the CNAS think tank, estimated the US could supply 20-50 units.The US Navy has only ordered 57 for 2026, an insufficient number for its manufacturer Raytheon to quickly ramp up production, according to German missile researcher Fabian Hoffmann. They would therefore have to be taken from US stocks.Ukraine would also rather launch the missiles from land rather than sea but the land-based launchers are in very limited supply: the US Army currently has only two batteries of four launchers, and the Marine Corps only four.- No game changer – Like the battle tanks or the F-16s and Mirages already sold to Ukraine, the Tomahawk is not “a wonder weapon that is going to win the war,” Pettyjohn wrote on X while adding that they have “have a notable strategic and operational effect”.”I don’t believe that a weapons system can radically change the situation in Ukraine,” agreed the head of the French Army, General Pierre Schill.Especially since, with the homegrown Flamingo cruise missile, “the Ukrainians have developed deep strike capabilities, which they built themselves and are now using on the ground,” said Schill.- Warning to Russia – Schill said the possible delivery of Tomahawks is “above all a political and strategic signal from Mr Trump to Mr Putin to say ‘I told you I wanted us to move towards peace, I am ready to support the Ukrainians'” if there is no progress.Putin has warned that the supply of Tomahawks to Kyiv would constitute a “whole new level of escalation, including in relations between Russia and the United States”.Trump on Wednesday described the Tomahawk as an “incredible weapon, very offensive weapon”.”Do they want to have Tomahawks going in their direction? I don’t think so,” he said.